The notion that modern individuals bear heavier economic burdens than their Paleolithic predecessors collapses under scrutiny, as the latter’s economy—anchored by a single earner capable of provisioning entire groups through communal foraging and hunting—exposes contemporary society’s inflated sense of labor complexity and ownership entitlement; while today’s fragmented specialization and labyrinthine property laws parade as progress, they often translate into increased individual workload and social fragmentation, starkly contrasting with the minimalist, shared resource model that not only ensured survival but fostered collective responsibility and mobility without the baggage of permanent possessions or convoluted status symbols. Tokenizing real estate, a recent innovation, attempts to break down ownership barriers through fractional ownership, but it still reflects the complexities modern society has embraced.

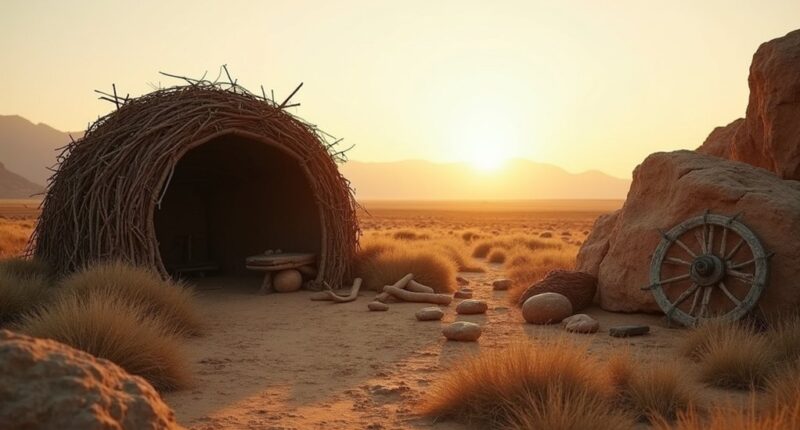

A single Paleolithic provider’s ability to procure sufficient sustenance for an entire community, coupled with the communal sharing of tools and resources, rendered the concept of ownership fluid and functional rather than a source of endless dispute and debt. The early adoption of wheel technology, far from the private, commodified assets they are today, belonged to families or individuals but was deployed for the community’s benefit, enhancing mobility and resource transport in a way that modern society’s rigid property rights and financial entanglements can scarcely emulate. Paleolithic shelters, ephemeral and constructed from readily available natural materials, served immediate protective needs without the crippling permanence or legal entanglements of modern homeownership, which often demands decades of labor and financial servitude. In fact, the physical traits of early humans, shaped by their environment, facilitated survival in diverse climates through adaptations such as body shape and heat regulation, underscoring a direct connection between biology and lifestyle in that era (climate-related adaptations). Physical health, too, thrived on the direct link between exertion and survival, a stark contrast to today’s sedentary lifestyles burdened with chronic ailments spawned by technological convenience. Their daily activities incorporated a high level of physical activity, which promoted muscle strength and coordination essential for survival. As brain and body size diminished alongside social complexity and technological reliance, the Paleolithic individual retained a coherent, communal existence unshackled by the modern paradox: possessing more yet laboring harder, owning less yet drowning in complexity. Modern life, in all its vaunted sophistication, has stolen the elegant simplicity and social cohesion that a single Paleolithic earner effortlessly embodied.